Written submission to The Joint Committee on Human Rights Call for Evidence in respect of Freedom of Expression

Submitted by Jane Fae for Trans Media Watch, 31 January 2021

Download this article as a PDF

Summary

- Our thanks to the Joint Committee on Human Rights (JCHR) for inviting contributions on this key subject.

- Trans Media Watch is the UK’s premier organisation focused on how news stories concerning trans and intersex people and issues are reported. As such, we will in this response argue that a perspective that focuses entirely on some abstract aspiration labelled “free speech” cannot be meaningful without regard to the wider public context within which speech now operates.

- Referenced within our response is recent work we have carried out on media tropes and issues. These were documented more fully in a recent submission to the Women & Equalities Select Committee (WESC) in respect to the GRA, and we would be happy to make that submission available also to the Joint Committee as and when we are granted leave to publish it by the WESC.

- We arrive at this inquiry with three significant concerns:

- That your call for evidence appears to reflect a moral panic raised over the issue of “free speech” by a number of influential individuals and organisations with a vested interest in a certain “free speech absolutism” or “consequence-free” speech, rather than any real problem on the ground

- That in addressing the issues according to this framework, you are giving more than tacit support to an already privileged class of people and organisations whose primary concern is not freedom of speech but their freedom to comment on current affairs and shape public opinion untrammelled by any real counter-argument or criticism

- That the framework within which the JCHR appears to be working is but one way of viewing the free speech issue, and it is concerning that there appears to be little evidence that it is aware of, let alone prepared to consider alternative frameworks

Introduction and Perspective

- We would like to thank the Select Committee for inviting evidence on this issue. Although, as we set out below, we consider it to be primarily a pre-occupation of the media and of a relatively small but vocal sub-set of the UK population, such as Toby Young’s Free Speech Union.

- This evidence is hereby submitted on behalf of Trans Media Watch, which is a charity dedicated to improving media coverage of trans and intersex issues. We are the premier group working in this area, being one of the few LGBT organisations in the world dedicated to working with the press.

- Over the last decade, we have made consistent interventions in respect of policy, contributing to the Leveson Inquiry and this Committee’s 2017 inquiry into Freedom of Speech in Universities as well as various inquiries by the Women & Equalities Select Committee into issues facing trans people. We have engaged with the Law Commission’s consultations on Online Harm and Hate Crime and worked with the press regulator, IPSO, when that organisation looked into reporting on press coverage of issues relating to trans people. Both of these engagements are relevant to the response we provide here. We have also worked with Ofcom, the BBC, the BBFC and the Advertising Standards Authority.

- In this submission, we have responded in two ways.

- First, we have responded, question by question, to your own call for evidence. Some sections have attracted more comment than others because they are more relevant to our own expertise than others, and we are a firm believer in “sticking to our knitting”.

- Second, we have responded with questions of our own. It appears to us that the concerns expressed in this inquiry reflect a particular paradigm that are more to do with a media-fostered moral panic than anything occurring on the ground. And we are concerned at the apparent “capture” of this issue by a perspective on free speech that would rightly, even ten years ago, have been regarded as extreme and reactionary.

Committee Questions

Does hate speech law need to be updated or clarified as shifting social attitudes lead some to consider commonly held views hateful?

- This question appears to be straight out of a certain type of reactionary media playbook, and to be honest we are not entirely sure what it references, since there are no explicit Hate Speech Laws in the UK. What we have are laws relating to hateful conduct, such as incitement and harassment, of which speech may form a part.

- Malicious Communication comes close to fulfilling the definition of a “hate speech law”. However, following guidance from the DPP, the bar for any prosecution is high and depends on the impact of the words used, rather than the words themselves.

- The Law Commission is currently undertaking a review of Hate Crime Laws. This highlights that different levels of protection exist depending upon protected characteristic. However, in general, Hate Speech is not a thing, relating to the criminalisation of specific words or speech. Rather, it is a chimera: a bogey of the right-wing press, but not at all a thing that exists in everyday operation. As such, we are concerned that so esteemed a body as the JCHR should make reference to it as though it were.

- We have repeatedly made clear that we are not concerned with “offence” or “offensive speech”, per se. We do not believe in, or wish for, any form of law that criminalises speech just for “offence”. We consider the final clause in the question posed – referencing speech that “some may find hateful” – to be misleading and redundant.

- We do, however, consider that repeated pursuit of an individual with a view to insert views into their daily experience after being asked to desist is an issue and the test, as set out in current law should continue to be not whether a court finds particular phrases to be “offensive”, but what impact such pursuit has on the individual. Specifically, it should be asked whether such conduct gives rise to an action for Harassment.

- We were, therefore, puzzled by the Miller case in February last year, as well as the more recent Scottow appeal. In both, judges appeared to make the test of whether or not the law had been broken into a question of whether or not words used were offensive. In both, the outcome led to the press re-affirming that there IS a “right to offend” in the UK.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-lincolnshire-51501202

- This, though, seems completely to miss the point, as in both cases, the complainants expressed distress at the repeated use of words designed to embarrass or humiliate them. If, therefore, we have a concern on this front, it is that the courts are paying insufficient attention to the effect of words, choosing instead to focus on the words themselves.

Does current police guidance and practice on hate speech law help promote freedom of expression?

- We assume this is in respect of the Miller case. Again, this conflates operation of Hate Speech Laws (not engaged here) with that of the notification and recording of Hate Speech incidents (cf. also a current case re. a teenager). In the Miller case, it was argued that the manner in which police communicated with the plaintiff was excessive and “disproportionate”. We have considerable sympathy with that point of view.

- In follow-up interviews with the media, Jane Fae (chair TMW) and Helen Belcher (Trustee) made clear our concerns that such policing might be intimidating, as this would constitute a form of double jeopardy. Therefore, where the function of police is to have words with an individual passing on concerns as to behaviour, this should be executed in such a way as not to expose an individual to additional penalty.

- Doing so in front of work colleagues is clearly a matter of concern, and police should think carefully about the consequences of doing so. However, it should not be ruled out. Otherwise any individual who suspects they might be about to be asked to speak with police, would make it very hard for police to find them. Clearly it cannot be the intent of the law that the police’s ability to do their jobs should be capable of being foiled by so simple and transparent a tactic.

- Equally, only permitting police to speak with members of the public when a law has been broken would severely limit effectiveness. There must be scope to have words to encourage individuals to moderate behaviour that is not unlawful but trending towards, to de-escalate and head off a potential infraction.

- Additionally we have seen and commented on a number of stories about cases where police have had words with individuals who, it is suggested, have made transphobic commentary or postings. Little illustrates better a theme to which we will return later – of framework – than this. For the stories are almost always sensationalised. Press that ordinarily would be full of “if you don’t want to do the time, don’t do the crime” switch to heart-wrenching pictures of individuals complaining that police spoke to them “in front of their four-year-old”.

Is there a need to review the wording and application of Public Space Protection Order (PSPO) legislation?

- We consider this to be mostly outside of our remit, and therefore not a matter on which we shall comment, beyond this: while PSPOs are about conduct in a public space, it is clear from the subject matter covered off by many that they may also cover speech or “speech acts”.

- This highlights what may be considered a serious case of government double standards, whereby nothing that impacts upon free speech in universities may be tolerated: yet at the same time, free speech that gives offense may be barred. The common factor in both these instances is the group impacted: in the first case, it is privileged individuals, used to having a platform, fearful of losing that platform: in the second, it is these same individuals unhappy at being exposed to awkward views.

What obligations does an employee have to their employer when expressing views on social media, and to what extent can, and should, employers respond to what their employees say on these platforms?

- Employers have obligations to customers, employees and, where they are a limited company, to shareholders. There are therefore good reasons for not permitting employees to conduct themselves in ways that might impact upon bottom line by driving away customers, or alienating staff; and in terms of their obligations to maximise shareholder value, they might be in dereliction of their legal duty if they do tolerate it.

- It is clear that the public expression of employee views has consequences, as Gerald Ratner found out with his infamous prawn sandwich “joke”. Employers need, therefore to be aware of what employees are saying

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2009/mar/07/gerald-ratner-interview

- There is also the wider issue of employees bringing an organisation into disrepute. The public will ask whether an organisation that tolerates individuals with certain attitudes is an organisation that can be trusted on wider issues. We hesitate to intrude upon private grief, but we note that the Labour Party, in respect of anti-semitism, as well as the Conservative Party in respect of Islamophobia, both consider it wholly their business what statements party members, even ex-leaders, put into the public domain.

- We would also suggest that making a point of expressing certain views is evidence of attitude, which is fair to bring into review of employment. Because an individual expressing views that indicate disdain or contempt for any particular customer group – not just protected characteristics – can be assumed to allow these feelings to intrude into the way in which they treat those individuals.

- Given the way in which trans people have been identified in some sections of the media as “enemies of free speech”, we wonder if this question is reference to the Maya Forstater case. This is widely represented by various media commentators, including J K Rowling, as “fired for saying x”. This is a common trope amongst free speech proponents: to seek to minimise or belittle the facts of the case brought against individual.

- To be clear, she was not “fired”: her freelance contract was not renewed – a common experience for contractors. This followed a wide range of online postings up to and including a declaration that she believed it her right to address any colleagues or clients of the organisation for which she was working according to her own view of their personal status, and irrespective of their own wishes, in a way that would likely cause upset. In short, she proposed offending and potentially harassing a subset of customers and colleagues without sanction. And while, as above, we do not believe “offence” should be the yardstick, an employer cannot disregard the stated intention of an employee or contractor to do so.

https://www.gov.uk/employment-tribunal-decisions/maya-forstater-v-cgd-europe-and-others-2200909-2019

- By way of corollary we reference a case from the US, which is even more wedded to free speech absolutism than here:

https://www.pinknews.co.uk/2020/12/23/corrections-worker-fired-facebook-transgender-inmate/

Is greater clarity required to ensure the law is understood and fair?

- To the extent that some people misunderstand the law, and others misrepresent the law as other than it is, we agree that greater clarity is always a good thing.

- In this case there does appear to be an issue, in the sense that the press constantly reference “hate speech laws”, either as useful shorthand or in furtherance of a particular political-correctness-gone-mad agenda, leading people to have a significant misunderstanding of what is and what is not criminal behaviour.

How has the situation changed in universities in the two years since the Committee’s report on the issue?

- Again, this is mostly outside our remit (notwithstanding that we gave evidence last time round based on our own experience of no platforming). We are also not entirely clear what “the issue” is, referred to here: does the JCHR mean no platforming?

- Obviously, we believe the situation has changed and for the worse. Our experience is that many major media outlets have promoted a moral panic focused on “no platforming” or, more recently, “cancel culture”, encompassing a range of things, not all problematic. E.g. speakers not wishing to share a platform with certain individuals, or audiences not wishing to attend specific events, as well as demonstrations against particular speakers.

- Insofar as criticism of demonstrations has any meaning, this appears, again, an attempt to shut down a particular form of protest by tone policing: the “proper way” to do debate is to “be” an internationally acclaimed expert on a topic, whereupon you will be handed a microphone and allowed to get on with it.

- We note the recent publication of Cambridge University’s free speech guidance, with known issues:

This, however, has been soundly criticised by a number of academics, including Priyamvada Gopal who warns that “Free speech can become a Trojan horse to gain space and attention for retrograde ideas”. She further argues that reforms designed to “safeguard” speech are likely to have the opposite effect, placing the power to decide what is “acceptable speech” in the hands of a small, select elite.

https://www.theguardian.com/profile/priyamvadagopal

- There is a central hypocrisy here: to offend is fine: yet to protest against offence is not. This contrasts with the UN Declaration on Human Rights, which regards free speech as a qualified right which must be balanced by the right to protest. Again, we see increased willingness to clampdown on individuals and organisations seeking to exercise their right to demonstrate, compounded by media spin that presents demonstration as illegitimate: basically, “one law for the privileged, another for everyone else”.

Does everyone have equal protection of their right to freedom of expression?

- Our simple answer to this is: no. In large part, this is a framework issue, which we address in the next section.

Critique of Inquiry Framework

- Far from seeing any crisis of free speech, we regard what is going on now in academic institutions and elsewhere as indicative of old-fashioned rumbustious discourse – often messy, on all sides.

- Ranged against this is a privileged class that has, historically, monopolised intellectual development by an intrinsic bias toward the idea that the proper development of ideas is within the (established) academy and, increasingly, within the opinion columns of the “respectable” national media and flagship programmes such as Newsnight on the BBC.

- In effect, defence of free speech has become a situation wherein a privileged class protects its right to dominate discourse on pretty much every issue in the UK. According to Jodie Ginsberg, until 2020 CEO of Index on Censorship: “Freedom of expression is a universal value and one that should be protected for all. The value should not be emptied of worth and meaning by those who use it as a rallying cry to defend only a single discourse and who use their own free speech to prevent others from speaking”.

- We have arrived at a crossroads, perhaps the apogee in a journey from a situation where speech is regarded as having consequence to one where we are told no consequence need be considered.

- Under guise of protecting free speech, we increasingly see minorities denied a voice. This begins with a denial of the validity of protest: argument that the latter is an act that “could” lead to violence is transparent in extreme, since this is precisely the concern expressed when minorities complain of speech used to harass individuals. Again, though, the first “concern” is treated as significantly more valid than the second.

- What we are also seeing is a double standard, according to which established commentators (privileged members of the kyriarchy, as an intersectional analysis would put it) complain of being “cancelled” or harassed, even though the cancellation and harassment is minimal, while minorities struggle to achieve a voice anywhere. As distinguished feminist Kath McKinnon put it: a level playing field does not lead to equality; it merely entrenches those with already established power and privilege.

- In terms of “cancellation”, we see columnists such as Suzanne Moore losing position because they take issue with the idea that they might be subject to editing – and then being mightily “cancelled” in the pages of The Spectator, Daily Mail, Telegraph, to name but a few.

- There is much talk, too, of the “cancellation” of J K Rowling, or indeed of her being subject to abuse. On the first, it would appear that certain demographics are no longer fans of her work. If this is cancellation (akin to the Cambridge University free speech rules), then we appear to have arrived at a place where the right of an individual to refuse to read output or engage in debate with certain authors is curtailed for the sake of (those authors’) free speech.

- As for negative comment on social media, we must distinguish two factors. On the one hand to receive threats and abuse is wrong and needs to be dealt with by relevant authorities. However, the volume of adverse comment, often commented on by the media, is a media red herring. Ms Rowling has 14 million followers on Twitter: more people than live in several EU countries, including Belgium. The real issue here is that if you have a significant public footprint, then you will attract significant commentary, both good and bad.

- Meanwhile, individuals with counter-experiences are generally considered less valid and given less airtime and media space. For instance, debate over trans people (usually shorthanded as “issues”) largely omits actual trans people: in one major national newspaper, just 5% of content referencing trans news stories includes trans comment. Equally, the Times, which must be considered impactful, published 324 trans-related stories and comment pieces in 2020 with, as far as we are aware, not one being given to a trans person to write. Issues were framed almost exclusively from an anti-trans perspective: and where trans people were quoted at all, a variety of devices were employed to diminish their status as commentators.

- In addition we find it incredible that this Committee can consider this issue without at very least expressing some curiosity as to the impact of libel laws, supported by both the IPSO and Impress Editors’ Codes. These exclude groups from the discrimination clauses, with the result that while the press must be very careful what they say about an individual, while broad-ranging attacks on minority groups can be unleashed at will.

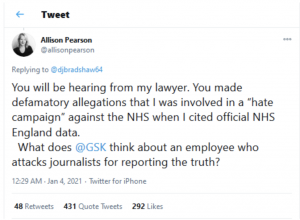

- Twitter is a place where much rowdy, robust “debate” takes place, but we believe we are not alone in observing a trend whereby individuals in positions of power use their relative privilege to silence any adverse view. One example of this took place earlier this month when a prominent (Telegraph) journalist responded to intemperate criticism by threatening to out an individual and to lose them their job:

https://twitter.com/allisonpearson/status/1345890182424391681

- In respect of commentary on issues affecting trans people, a few months back we noted online conversations between individuals which we would characterise as “transphobic” gloating over the absence of legal definition of that word and implying that they would pivot off this fact to make individuals and media organisations wary of using a word like “transphobic.”

- Since then, we have seen threats of litigation by J K Rowling, against a Canadian journalist for describing her as “transphobic”, as well as against a UK website organised by the Department of Education.

- We have also seen other people with a high profile and significant privilege using libel in this way to shut down debate. For instance, several members of political parties have attempted to regulate internal party debate not by rebutting comment, but by threatening to sue anyone who suggests they are transphobic.

- In late January 2021, after a journalist suggested he might be anti-trans, as it would appear many trans people believe him to be, actor James Dreyfus demanded a “retraction and apology,” or he would continue with legal proceedings.

- We are further concerned that one individual who has taken this approach to criticism is a member of this Committee, recently on Twitter demanding contact details of anyone who had termed her “transphobic”, with a view to “seeking redress”.

https://twitter.com/joannaccherry/status/1332756422963113984

- To be clear, there is no objective reality in terms of a single underlying concept that can be considered transphobic, any more than homophobic, misogynist, racist or any other. A good explanation of an increasingly accepted view of transphobia is provided by TransActual:

https://www.transactual.org.uk/transphobia

- However, it is objective reality that a significant proportion of any given community may hold a view that the net effect of an individual’s words and deeds may be harmful and as such, they ought to be entitled to state that sense. However, a concerted campaign against the use of certain words – such as transphobic – has led to a significant silencing of opinion within the trans community.

- In a similar way, it is widely recognised by a multitude of international studies that failure to address trans healthcare needs, particularly among young trans people, leads to significant adverse outcomes, including suicide. However, a media campaign insists that any reference to this fact is merely “weaponising” suicide. This means that major groups that are trans supportive (e.g., Good Law Project) will now not speak about this and, more widely, it is nigh on impossible to reference this as a serious issue in any public discussion of healthcare.

- Those who view trans as the Cinderella minority, the one of lesser importance, may not be so concerned. We believe this to be a mistake, however, as attacks on trans people are very much the canary in the coal mine, and it should be of concern to all on this committee if the UK were to move to a position where it is up to the perpetrator of a particular comment to determine whether the target of that comment should or should not consider it problematic.

- In this vein, we have lately seen use of libel laws in an attempt to silence black people calling out racism or LGBT people, more widely, denouncing homophobia. We do wonder what those members of this Committee who hold to a feminist analysis of society will do when, inevitably, the same tactic is used to silence individuals calling out misogyny.

- In conclusion, we do not see much of an issue regarding free speech in the UK right now, at least not as described in the media. What we are seeing is a serious imbalance in the established ways of moderating discourse, and a backlash from those used to having their say on issues with little genuine counter-balance.

- At the same time, we see a serious silencing of minorities, through exclusion from the media, and through the increasing weaponisation of libel laws. There are issues here that the JCHR needs to engage with: but not, we believe, the ones on the consultation.

Appendix I: Tweets

1.

- Tweet by Allison Pearson:

You will be hearing from my lawyer. You made defamatory allegations that I was involved in a “hate campaign” against the NHS when I cited official NHS England data. What does @GSK think about an employee who attacks journalists for reporting the truth?

https://twitter.com/allisonpearson/status/1345890182424391681

Leave a comment